가사 및 자녀돌봄 서비스 이용과 부부 간 노동 분담의 관계

Gender Differences in Contribution to Domestic Work and Childcare Associated with Outsourcing in Korea

Article information

Trans Abstract

This paper examines the associations of having a helper for domestic work or childcare and time spent on it by couples in South Korea. We use five waves of panel survey data from the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families (KLoWF), which allows longitudinal changes within couples over time that account for potential selection effects and unobserved heterogeneity among individuals. With fixed effects, we find outsourcing is associated with a decrease in wife’s time spent on domestic work or childcare by 1 hour per week. However, the decrease is concentrated on the unemployed wife’s time, but not employed wife’s time. In addition, outsourcing is not a significant factor for husband’s time and the husband’s share of total contribution. This may be because wives are the main provider of domestic work and childcare in Korea regardless of employment status or having any helper. Due to unequal contributions between husband and wife, using outsourcing also neither alleviates the employed wife’s contribution nor changes the husband’s contribution. However, the results may be underestimated because there are more common and diverse types of outsourcing in a broad sense, such as going out for dinner, buying prepared food, and using dry cleaning services. We expect future studies to consider more broad types of outsourcing and examine how relations with the couple’s time use at home are different by type.

Introduction

The socioeconomic status of women has considerably improved in South Korea due to rapid economic progress. For example, the number of women that had have bachelor’s degrees increased from 1.6% in 1970 to 40.0% in 2015. The college entrance rate of women was estimated at 32.4% in 1990 but has increased to 73.5% in 2017 and is now higher than men (66.3%). However, at the same time, married women are still expected to be in charge of domestic work and look after children at home. In comparison with other East Asian countries, employed Korean wives are likely to work much longer, whereas the division of domestic work is the least egalitarian, as Korean men are in favor of traditional divisions of household work (Oshio et al., 2013).

The traditional roles of women in Korea are due to Confucianism, the most important sociopolitical ideology for 500 years in Korea. It has unequal gender norms that clearly define the hierarchical role of men working outside the home, and with women assigned to doing housework, raising children and taking care of the elderly (Fuchs et al., 2018; Moon, 2012). Despite westernization and modernization in recent decades, traditional gender roles are still prevalent: men are the primary wage earner with women’s employment regarded as secondary (OECD, 2017). In addition, the working environment is hostile to married women in balancing work and family life. Data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2018) shows that annual hours worked in Korea are the third-longest among OECD members. Considering working hours of small firms, overtime hours (12 hours per week) and additional hours during the weekends, the average hours worked in Korea are expected to be longer in reality than the OECD estimates (Sung, 2017). As a legacy of the rapid economic development and Confucianism, working hard and long is still considered virtuous and loyal in Korea (Ko, 2007).

Higher education and employment rates for women conflict with traditional gender roles and values; therefore, one strategy to deal with housework and childcare, is outsourcing. Choi (2016) reports that 25% of married women aged 15 to 49 with children receive help from their parents for housework or childcare. In particular, married couples with young children receive support from parents, while they depend on nurseries and kindergartens as children get older.

Despite the prevalence of domestic outsourcing in Korea, limited research has investigated the relationship that outsourcing has on reducing the demand for housework and childcare with the contribution that a husband and wife each spend on housework or childcare. Our paper makes several contributions to the literature. First, this paper is the first to examine associations between having a helper for housework or childcare and time spent on it by married couples. Given prevalent gender inequality in Korea, we also examine differential associations by the wife’ s employment status. We also provide estimates on the husband’s relative contribution to domestic work compared to the wife’s in five types of housework. In addition, we separately examine the analysis to examine how each form of outsourcing for childcare and domestic work is related to a couple’s time. With eight years of panel survey data, we use fixed effects on individual for all regression models. This allows longitudinal changes within the couples over time accounting for potential selection effects and unobserved heterogeneity among individuals.

Literature Review

More women are employed and continue to take responsibility for domestic work; however, Goode (1960) argues four strategies may ease their role constraints: (1) separating work and family life (compartmentalization), (2) outsourcing household works (delegation), (3) reducing roles by having fewer children or quitting her job, and (4) finding a job that allows her to balance work and childcare. Most research since the 1980s has focused on the division of domestic labor between a wife and husband that develops and tests three major theoretical approaches: the relative resources approach the time availability approach, and the gender role attitudes approach. The central assumption is that household labor should be divided between spouses (Hook, 2006), depending on income, time, or attitudes toward gender equality. Several studies find that women’ s domestic work has decreased, while men’s domestic work has gone up (Altintas & Sullivan, 2016; Fuwa, 2004; Sayer, 2005). The increased amount of domestic work done by men is only marginal; therefore, women are still in charge of doing work at home despite the continuing trend towards gender equality in housework (Geist & Cohen, 2011; Sullivan, 2006; Zhang, 2017).

Raz-Yurovich (2014) argues that family members choose to make domestic production as well as outsource domestic activities. The relative cost of domestic works and childcare has decreased due to improved education (Hazan & Zoabi, 2014) or increased maternal employment (Vandelannoote et al., 2014) in post-industrial societies; however, workfamily conflict for couples has increased. The outsourcing of domestic work or childcare has become a crucial strategy to avoid conflicts between work and family roles (Hochschild, 2003). In European countries, Hank & Kreyenfeld (2003) suggest that the availability of public childcare arrangements is a more important factor in outsourcing childcare than cost. Outsourcing and subcontracting of domestic care and familial care to caregivers has also increased in several developed Asian countries, in addition to the expansion of the role of the market and voluntary sectors in care provision (Michel & Peng, 2017). Outsourcing domestic work or childcare has become common in Korea, particularly by hiring migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan (Chan, 2005; Choi, 2016; Constable, 2007; Cortés & Pan, 2013; Islam & Cojocaru, 2015; Lan, 2003; Estévez-Abe & Kim, 2013). Recent studies have shown that the frequency, specificity, and uncertainty level of the transaction, as well as social beliefs and preferences can facilitate or hinder outsourcing (Raz-Yurovich, 2014; Kornrich, 2012; Van der Lippe et al., 2012).

Several studies examine how outsourcing affects family members. Empirical studies suggest that buying domestic services leads to greater gender equality at home in reducing time shortages and subjective time pressure (Bergmann, 2005; Bittman et al., 1999). In the Netherlands, domestic help reduces women’s time spent on cleaning by about 1.5 hours per week, but it does not have any effects on men’ s time (Van der Lippe et al., 2004). However, time gains from purchasing housework services are marginal in France (Windebank, 2007), the U.S. (Killewald, 2011), and UK (Sullivan & Gershuny, 2013). Craig & Baxter (2016) use cross-sectional data in Australia to find that the husband gains more than the wife from paid domestic help; however, there is no indication that paying for housework alleviates the unequal gender division of housework and couples’ feelings of time pressure.

Housework is more unequally divided between men and women in East Asia, and the burden is heavier for women compared to Western countries (OECD, 2012). Cheung (2014) uses propensity score matching to show no significant association on how hiring domestic help is related to an employer’s family well-being in Hong Kong. Hsu (2010) shows that the woman is a major provider of domestic work, while her mother or mother-in-law are helpers for it in East Asian countries. The study also suggests that these informal helpers for household work can ease the burden of housework for both men and women, but ultimately reinforces the traditional gendered division of labor in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan (EstévezAbe & Kim, 2013). A comparative study of Iwai (2017) in Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan suggests that husband’ domestic work frequency is associated with working hours of the wife and husband, as well as with the presence of alternative resource such as the availability of husband’s mother.

Korean researchers have also studied the unequal division of household labor between wife and husband. Heo (2008) finds that time use for domestic work of married couples is significantly related to working hours and gender role attitudes. However, Eun (2009) concludes that a couple’s time availability and relative resources are more important factors that explain gendered division of domestic work than gender role attitudes. Kim (2009) finds that the gender division of labor in the United States and Korea that many women perform housework and childcare even when they are working, while many men do market work. This gendered division of work creates and reproduces disadvantageous situations for women in both countries. In addition, a few studies examine the relationship between the division of household labor and Korean women’ marital satisfaction (Cheung & Kim, 2018; Oshio et al., 2013; Qian & Sayer, 2016). Against the backdrop of low fertility, recent studies investigate how the division of domestic labor is associated with fertility desire or childbirth (Kan & Hertog, 2017; Kim, 2017; Yoon, 2017). However, none of them focus on the relationship between outsourcing and the contribution of husband and wife to housework or childcare. Cha (2015) finds employed wives spend more hours on housework outsourcing. A few other studies investigate the effects of outsourcing on different outcomes: Choi (2006)’ s study shows that a housework helper is associated with a decrease in double-income couples’ stress, but Jang & Jeong (2012) find that it does not have any association with a work and family balance.

Research Method

Data

We use data from the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families (KLoWF), a nationally representative survey of women in Korea. We pool data from five waves of data gathered between 2008 and 2016; however, we exclude data from 2007 since the questions related to outsourcing are different. KLoWF contains information regarding the economic activities, education, attitudes, family, and daily life for 9,997 women aged 19 to 64 who live in selected households across 234 districts of Korea. Only married couples living together are included in the analyses, since the unbalanced panel data provides different time constraints for divorced, bereaved, or separated couples; in addition, women who remarried in the middle of the surveys are excluded. Panels surveyed since 2008 as well as new panels involved later are included in the analyses.

Variables

To investigate our main question, “how much does a helper for household chores alleviate the burden on women and men?” we estimate OLS regression models with fixed effects for women, controlling for unobserved individual characteristics that do not vary over time. The outcome variable are minutes spent on domestic work (cleaning, laundry, cooking) and childcare by wife or husband. The answers are divided into time spent on domestic work and childcare since 2012, we add them together. We also add the relative contribution of husbands to domestic work or childcare compared to the total contribution by couples as a dependent variable.

Our independent variable is Outsourcing, which equals 1 if married couples receive help for housework or care for young children from family members, hired person, or any institutions, or 0 otherwise. The analysis includes working hours, and wage (won, 2015=100) of couples in regression models since couples demand outsourcing more when they work longer hours (De Ruijter & Van der Lippe, 2007) and earn more (Bittman et al., 1999; Cohen, 1998), which are also found to be associated with housework hours (Kamo, 1998; Nakhaie, 1995; Presser, 1994). Time spent on housework, wages, and working hours are recalculated as weekly; in addition, we also include if couples are in managerial or professional occupation. Previous studies show that income and professional occupation are significantly associated with a decrease in housework time as well as using outsourcing, because they are useful measures of resources contributed to the household (Craig & Baxter, 2016; Gupta & Ash, 2008). Since men who are least committed to relationships with spouses are likely to spend the least time on housework (Ciabattari, 2004), we include a measure for how frequent couple spend time together. The measure has four questions: “How often do you watch movies, performance, and sports game together with your husband?,” “How often do you go for a walk, hiking, or exercise together with your husband?,” “How often do you meet parents-in-law or siblings of spouse together with husband?,” and “How often do you meet your parents or siblings together with husband?.” Responses are ‘less than once every month,’ ‘once every month,’ ‘once every two weeks,’ ‘once every week,’ or ‘more than twice every week,’ summed to generate a relationship scale, with an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha (0.60). A higher score indicates that couples spend more time together.

We control for the number of children aged under age 6 and those over age 6 along with demographic characteristics such as age, age squared, and years of education for the couples. Our models are similar to the research of Craig & Baxter (2016)’s and Cornelisse-Vermaat et al. (2013)’s. 7,464 wives and 7,464 husbands are included in the analysis.

Strategy: OLS Regression with FE

The analytic strategy is OLS Regression with Fixed Effects on individual and year. The OLS regression with Fixed Effects controls unobserved heterogeneity among individuals. To understand how the contribution of husbands and wives to domestic work or childcare is associated with outsourcing, we estimate the following equation:

Yit = β0 + β1 Xit + β2 Outsourcingit + ηi + γt + εit

where Yit is weekly time (minutes) spent on domestic work or childcare by husband and wife, while Outsourcingit is whether the couple has outsourcing for domestic work or childcare. To see the relative contribution of husbands to domestic work or childcare, we have created another dependent variable that equals the percentage of minutes spent on domestic work or childcare by husband in total minutes spent by couple. Fixed effects on individual (ηi) and year (γt) are included to control for unobserved heterogeneity among individuals as well as time-variant and time-invariant unobservable variables. Xit are the number of younger (aged 0 to 6) and older children (aged 7 to 18) in households, the scale of couple’s spending time together, as well as wage, weekly hours worked, managerial or professional occupation, age, age squared, and years of education for the couple. All analyses are conducted using STATA version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

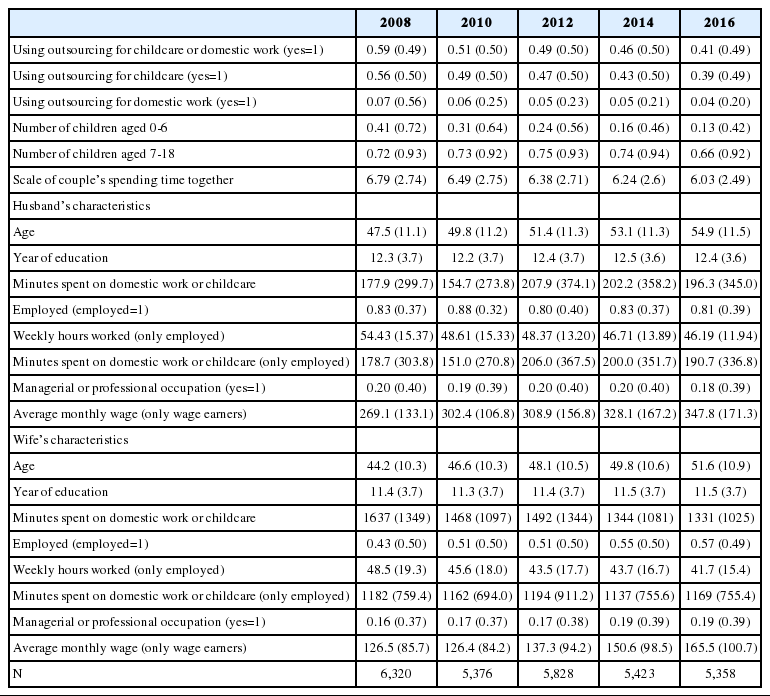

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of those who are married and living with spouses for each wave (2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016). While 80% to 88% of husbands are working, 43% to 57% of wives are working. On average, a wife spends 1,331 to 1,637 minutes (22.2 to 27.3 hours) for domesticwork or childcare per week, while an employed wife spends 1,137 to 1,194 minutes (19.0 to 19.9 hours) per week on average. However, a husband spends only 154 to 208 minutes (2.6 to 3.5 hours) for housework or childcare per week on average, which is not much different from the time spent by a working husband. The statistics show unequal distribution of unpaid work at home between wife and husband because the average weekly hours worked for employed wife and employed husband are similar. To handle with housework or take care of children, 41% to 59% of married couples depend on outsourcing.

Regression Results

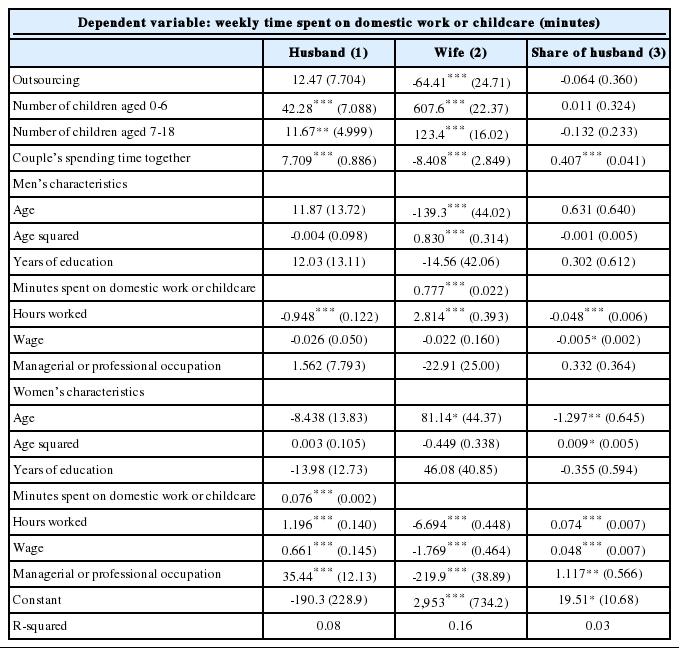

Table 2 reports the OLS regression results with fixed effects on individual and year, controlling all covariates. Dependent variable is weekly time (minutes) spent on domestic work or childcare by husband in column (1), that by wife in column (2), and relative contribution of husband in column (3). Using outsourcing for domestic work or childcare is associated with a decrease in the contribution of wives by 64.41 minutes per week, which is significant at the 1% level. However, outsourcing for unpaid work at home does not have significant associations with the total contribution of husbands as well as the relative contribution of husbands in the total contribution of couples. Although we do not report the results here, the estimates are similar when the analysis is restricted to women aged under 50, considering many young women use outsourcing for childcare. The number of young children under age 6 is positively associated with an increase in the contribution of husbands and wives. This is different from Craig and Baxter (2016)’s finding that the number of young children has significant associations with the contribution of wives, but not with husbands, who are more likely to contribute to unpaid work at home if their spouses spend more time on it. A measure of couple’s spending time together is statistically significant in all models: If couples spend time together more frequently, husbands are more likely to spend time on domestic work or childcare, while wives are less likely to spend time on it. Moreover, hours worked of husbands and wives are significant factors for both their own and spouse’s contributions. If they work for longer hours, they are likely to spend less time on unpaid work at home, but their spouses are likely to spend more time on it. We find similar evidence for the relative contribution of husbands in the total contribution of couples. Column (3) indicates that if wives work for longer time, their husbands’ share in domestic labor or childcare is likely to increase; however, if husbands work for a longer time, their relative contribution also decreases, which is consistent with Iwai (2017)’s finding in East Asia.

Fixed Effect Regression Analysis: Associations between Outsourcing and Time Spent on Unpaid Work at Home, Married Couples, South Korea, 2008-2016 (N =28,477).

However, there are some gender differences in time association with couple’s characteristics. If a wife earns a higher wage or works in managerial or professional occupation, she is less likely to spend her time on domestic work or childcare, whereas her husband is more likely to spend his time on it. However, husband’s wage and his managerial or professional occupation are not significant. In addition, wives’ time is sensitive to the number of children aged 7-18, but the husbands’ time is not.

Table 3 represents the results from Fixed Effect regression analysis that estimates differential association between outsourcing and couple’s time use by wife’s employment status. The dependent variable is the contribution by husband in column (1) and (2), and it is the contribution by wife in column (3) and (4). In column (1) and (3), the analysis is restricted to the couples with employed wives, while in column (2) and (4), it is restricted to those with unemployed wives. The results indicate that outsourcing is associated with unemployed wives spending less time in domestic work or childcare by 148 minutes per week. However, we do not find any significant associations for time of husbands and by the employed wives. This may be because wives are the main provider of domestic work and childcare in Korea (EstévezAbe & Kim, 2013) regardless of her employment status or having a helper. According to Cai & Lee (2004), there is no significant difference between married men with employed wives and those with non-employed wives in their contribution to domestic work. Descriptive statistics from our panel data also suggest that husbands with working wives do domestic work and childcare for 3.3 hours per week, while those with non-employed wives do for 3 hours per week. Due to unequal contributions to domestic work or childcare between husband and wife regardless of the wife’s employment status, using outsourcing also neither alleviate the employed wife’s burden significantly nor change the unequal contributions between husband and wife.

Fixed Effect Regression Analysis: Differential Association between Outsourcing and Time spent on Unpaid Work at Home by Women’s Employment Status, Married Couples, South Korea, 2008-2016.

Couple’s time spent on unpaid work at home is sensitive to wives’ wage and hours worked by couples, which is consistent with our results in Table 2. However, when we restrict the analysis to only the employed wives, couples’ time does not have any associations with whether wives’ managerial or professional occupation. In addition, whether couples spend time together for leisure or visiting families is not important anymore for working wives’ time on work at home. This may be due to the lack of time availability of married working women.

Table 4 reports the share of the husband in doing five types of domestic work (cleaning house, doing grocery shopping, doing laundry, cooking, and dishwashing) in the total contribution by both husband and wife. The questions are “How often do you do each domestic work per week?” which have five response categories: almost every day, 4-5 days per week, 2-3 days per week, 1 day per week, and rarely. The dependent variable is the percentage of the frequencies in doing each domestic work of husband in total frequencies of the couple. The estimates indicate that outsourcing for domestic work is not associated with changes in the husband’s share in any types of domestic work. The result is similar when we restrict the analysis to dual-earning couples. The number of children aged 0 to 6 is not a significant factor for the husband’s share of unpaid work at home except laundry. However, the number of children aged 7 to 18 is negatively associated with the share of husband’s contribution. These similar findings are suggested in Table 2: both husband and wife with young children are more likely to spend more time on domestic work or childcare, while the number of adolescents is positively associated with wives’ time, but not with husband’ s time. Hours worked by couples and wives’ wage remain as significant factors for all types of domestic work, which is consistent with the results in Table 2.

Fixed Effect Regression Analysis: Associations between Outsourcing and Relative Contribution of Husbands to Each Type of Domestic Work, South Korea, 2008-2016 (N =28,477).

To examine different associations by form of outsourcing, we separate the analysis for time spent on childcare and for that on domestic work. Only data from three waves (2012, 2014, and 2016) is included, because the question about couples’ time has been separated since 2012. The fixed effect regression results are reported in Table 5. The first dependent variable is minutes spent on childcare by husband in column (1), and those by wife in column (2). The main independent variable for these outcome variables is outsourcing for childcare. For childcare analysis, only married couples with at least one child under 18 are included. Second dependent variable is minutes spent on domestic work by husband in column (3), and it is those by wife in column (4). The main independent variable for these outcome variables is outsourcing for domestic work. The results are similar with those in Table 2. Two forms of outsourcing have significant relations with wives’ time: outsourcing for childcare and domestic work is associated with a decrease of wives’ time by 201 minutes (3.35 hours) and 131.1 minutes (2.19 hours) per week, respectively. However, they are not significant factors for husband’s time. The associations with covariates are slightly different from those in Table 2. Although husbands’ wage does not have any significant relations with total time spent on domestic work or childcare by either husbands or wives, it is associated with an increase in wives’ time only for domestic work. In addition, the husband’s employment in managerial or professional occupation is negatively associated with his own time spent on domestic work. On the contrary, time spent on separate unpaid work becomes less sensitive to wives’ managerial or professional occupation compared to Table 2.

Conclusions

Limitations

The main limitation of our analysis is that we use information reported only by wives, since information reported by husband is not available. Several studies find that husbands and wives are more likely to overreport their contributions to work at home, but they underreport spouses’ contributions (Kamo, 2000; Treas, 2010). Therefore, using wives’ self-reported information may underestimate husband contributions to the time used for housework or childcare, which makes our estimates biased. Another limitation is that our number of observations for the results in Table 5 are different from those in other tables. This is because the question for time use for unpaid work at home has been separated into time spent for domestic work and childcare since wave 4.

Policy implications

Outsourcing has been a potential solution to the unequal division of unpaid work at home. However, there are no previous literature studies on how outsourcing is related to workload at home of men and women in Korea, where gender inequality still persists. The results show the longitudinal changes within couples in contribution to domestic work or childcare when they use outsourcing, including different forms of outsourcing. Outsourcing use is associated with a decrease in wife’s time spent on household work or childcare by 1 hour per week. However, outsourcing is not related to any changes in the share of a husband in domestic work or childcare, as well as five types of domestic work. This finding is consistent with a study in the Netherlands, which finds that domestic help reduces women’s time on cleaning by about 1.5 hours per week, but it does not have any effects on men’s time (Van der Lippe et al., 2004). When separating the models into time spent on domestic work and that on childcare, both outsourcing for childcare and for domestic work have significant associations with a decrease in wives’ time. In addition, outsourcing is not associated with employed wife’s burden for domestic work or childcare, since she is still the primary provider in Korea regardless of employment status (EstévezAbe & Kim, 2013). Overall, having a helper for housework or childcare is associated with women’s time saving, but the amount is marginal.

Expectations for traditional gender roles and the lack of support makes it difficult for married women to balance work and family life. We should stop placing women in the role of primary caretakers for households and support husbands in sharing more responsibility at home, so that they can keep their work and family at the same time. First, national and local governments need to offer more effective and affordable outsourcing for childcare. In particular, they need to provide affordable public childcare services for young children under age 6, given that the number of children is significantly associated with both mothers’ and father’s time. The services should be available for whole day, since dual-income couples and multi-child households need help for a longer time. At the same time, married couples, especially working women, need to consider more diverse way to outsource domestic work or childcare to ease their burden at home.

The results also indicate that hours worked of couple are significantly important factors for husband’s contribution to unpaid work at home. Governments and companies should allow couples to spend more time with family members by reducing time at workplace and providing compulsory and non-transferable parental leave since Koreans work the third-longest hours of OECD member countries. Deeprooted cultural norms that value working long, or women as the main providers for domestic work and childcare should be changed to achieve gender equality at home.

It is important for married couples to build more intimacy and sense of connectedness. Husbands who spend more time with wives for activities also invest more time on domestic work or childcare and wives do less. It is suggested that married couples spend more time together to enjoy leisure or diverse activities. The results indicate that working wives cannot save their time from using outsourcing because the contribution of husbands is not different by wives’ employment status. Therefore, husbands whose wives are working are required to spend more time doing domestic work or taking care of children.

To improve the country’s productivity and the fertility rates, Korea’s National Assembly passed a new law reducing the maximum weekly working hours from 68 hours to 52 hours in March 2018. Future studies should find evidence that this new law changes couple’s time use at home and changed the unequal division of domestic work and childcare. There is also a need to examine if differential associations with the couple’s time saving exist according to different type of outsourcing, such as hiring a person and for receiving unofficial help from parents or relatives. In addition to helper, there are more common and diverse forms of outsourcing, such as going out for dinner, buying prepared food, and using dry cleaning service. Craig & Baxter (2016) show that dry-cleaning and gardener or maintenance services are associated with less male time towards domestic work, but not with women’s domestic work time. The study results may be underestimated since these types of outsourcing can also substantially decrease time used for unpaid work; therefore, we expect future studies to consider broader forms of outsourcing and examine how its relations with the couple’s time use at home are different by each form.

Notes

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the authorship or publication of this article.